Publicité

New Delhi’s strategic calculus over Agalega

Par

Partager cet article

New Delhi’s strategic calculus over Agalega

Agalega is back in the news, after it has been linked to the ‘sniffing’ affair currently roiling Mauritian politics and landing New Delhi in a geopolitical soup. As the Agalega question once again takes centre stage in parliament, Port Louis is finding it harder to convince its own people that this is just about infrastructure. For India, Agalega is all about the strategic Mozambique channel and the natural gas bonanza off the coast of Mozambique.

1. Chokepoints and the change in Indian military thinking

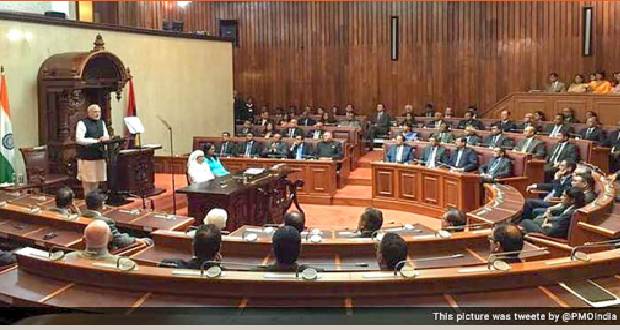

The deal between India and Mauritius over an Indian military base on Agalega is back in the news, both as a result of the ‘sniffing’ scandal that is embarrassing New Delhi as well as the opposition returning to the Agalega question in the National Assembly.

Interest in Agalega as a potential military base dates back to the 1970s. “Even the Soviet Union had expressed interest in having a base on Agalega back in the day,” says ex-foreign minister Arvin Boolell. In April 1975, a Seychellois businessman, Paul Moulinie, said that he had been approached by Moscow to help them set up a base on Agalega, which was then run by a Seychelles-based company Chagos-Agalega Ltd that sold copra to a company in Mauritius. In October of that same year, Mauritius took over the administration of Agalega directly through a state company that in 1983 would become the Outer Islands Development Corporation (OIDC).

After briefly flirting with the idea of turning Agalega into a resettlement area for Chagossians – out of 421 Chagossian families in Mauritius, only eight wanted to go to Agalega – nothing much was done there. But it wasn’t just Moscow that dreamed of bases in Mauritius. K. M. Panikkar, India’s most influential maritime strategist, even before Indian independence wrote that “a true appreciation of Indian historical forces will show beyond doubt, that whoever controls the Indian Ocean has India at his mercy”. Panikkar advocated the eventual setting up of a “steel ring” of naval bases in Singapore, Mauritius, Yemen’s Socatra Island, and Sri Lanka to secure what future Indian leaders would refer to as India’s sphere of influence (Jaswant Singh) or its strategic footprint (Manmohan Singh). Influential as Pannikar’s ideas have been on Indian strategic thought, it was not until the 1990s that New Delhi was in a position to act on Panikkar’s ideas of extending India’s power seaward.

New Delhi’s maritime strategy

India’s economic liberalization and the resulting economic growth made it possible for India to start investing heavily in developing its navy. It was only in the mid-1990s that New Delhi announced its intention to develop a blue-water navy to safeguard its growing economic and trade interests in the region. “Before, even if India was interested in Agalega, it did not have the means or power to do anything about it,” argues Boolell, “but it was in the late 1990s that they really started showing interest in Agalega.” That was also the time that India really started developing its naval military doctrine. Indian military and strategic thinking has been a mix of four schools of thought: a continentalist school that identified India’s main threats to be coming from its land borders with China and Pakistan, and consequently funnelled the lion’s share of resources to the Indian army and air force at the expense of its navy. A Monrovian school that views South Asia and the Indian Ocean as part of India’s own Monroe doctrine. A Raj-school that inherited the British Raj’s view that the Indian Ocean was a single strategic space and lastly, the Soviet school that was influenced by Soviet naval doctrines that spoke of ‘area defence’ through controlling key chokepoints to keep out competitors.

It is this Soviet school that influenced India’s first-ever maritime doctrine in April 2004 which states, “Control of the chokepoints could be useful as a bargaining chip in the international power game, where the currency of military power remains a stark reality.” The 2007 edition of the Indian navy’s maritime strategy continued in the same vein. But it was in the 2015 update of its maritime strategy that the Mozambique channel, a 1,000 nautical-mile strip of ocean between Mozambique and Madagascar, was identified as a potential key chokepoint in the Indian Ocean and one of the Indian navy’s areas of primary interest.

2. The approaches to Mauritius

As India was settling on a strategy to control chokepoints in the Indian Ocean, that is where New Delhi openly started pushing to be allowed to set up a military base on Agalega. These approaches were masked in various ways, including setting up a tourism development owned either by India’s Tata or Oberoi group. The first such open request was reported by Indian newspaper back in November 2006. “That is when we know of Agalega starting to be discussed between India and the Times of India Labour-led government of Navin Ramgoolam,” explains Vijay Makhan, ex-foreign secretary and for mer OAU deputy secretary general. At the time, the Labourled government dismissed the reports - by insisting that the Indians were only talking about coming up with an economic development plan for the island focusing on coconut, fisheries and agricultural diversification. As well as possibly improving the runway there.

Then again in 2012 when Mauritius was in the midst of talks with New Delhi over its tax treaty – responsible for building up Mauritius’ financial services sector since 1991, but decried by India as depriving it of tax revenue. At that time, then-foreign minister Arvin Boolell was accused by the Indian press of offering Agalega up in return for keeping the tax treaty unchanged. “At that time, even Bollywood was showing Mauritius as a tax-haven and a round-tripping destination. The Indian press just misrepresented that and did not publish a rejoinder that the Mauritian government sent. There was no such offer,” says Boolell.

But with New Delhi insistent on being allowed into Agalega – where they had already set up a coastal radar – no agreement came of that. “At the time we were fighting about the Chagos, and did not want to send contradictory signals. Nor did we entertain any official requests for an Indian military base in Agalega, although I am sure this was discussed in the corridors, of repeating another Chagos as well as the counsel of figures, such as ex-Supreme Court judge ” says Boolell. It was the fears Rajsoomer Lallah, who had been the UN representative to Myanmar, that explained Port Louis’ reluctance to allow New Delhi to set up a base on Agalega. “ when it came to Agalega, We did not sign anything with India ” insists Boolell.

Indian pressure for Agalega was also being fuelled by two factors: firstly, the lack of development on the island provided a convenient cover for its ambitions. After 2003, the Mauritian conglomerate IBL pushed for regional tourism on the island, but opposition from the Labour Party shelved those plans. Then in December 2005, the South African company ARCON proposed a $450 million deal that included setting up tourism infrastructure, a wind energy plant, sewage, bungalows, a marina, restaurants and shops. That 2008 deal too fell through because ARCON asked for too much land – 400 hectares – for its project. Secondly, India was encouraged by fears that China was encircling it (‘the string of pearls’) and US encouragement that New Delhi take on a bigger security role in the region. In 2005, the Bush administration announced that it would “ the 21st help India become a major power in century”, and in 2008 when US navy secretary Donald Winter said that Washington welcomed India, “taking up the responsibility to ensure security in this part of the world''.

In 2016, India partnered with Japan to launch the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC), offering soft loans to African states to compete with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). That did not work and the AAGC was soon forgotten. Today that has come to fruition through the establishment of the QUAD grouping. “The purpose of the Western powers is to make sure that the Indian Ocean remains India’s lotus and to keep the Chinese behind the Malacca straits,” says Boolell.

3.One failure and one success

While New Delhi has wanted Agalega since the late 1990s, it was not until 2015 that it succeeded in getting it. As part of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s tour of Indian Ocean island states, he signed deals with Mauritius to set up a facility on Agalega, and with Seychelles for Assumption Island. Both Agalega and Assumption island are strategically located near the Mozambique channel and a key chokepoint identified by New Delhi with the Indian ocean.

However, when it came to Assumption Island, India faced a setback after a new government led by Wavel Ramkalawan ditched the 2015 deal over fears for Seychellois sovereignty and embroiling Victoria into a larger geopolitical confrontation. Agalega, however, proved to be a success. Just this week, Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth told the Mauritian parliament that the Indian company AFCONS Ltd had nearly completed a 3-km-long runway on Agalega – capable of running P-81 planes, as well as an extended 255-meter jetty, spending Rs8.8 billion.

Yet, while the Mauritian government is continuing to insist that India’s moves on Agalega do not have a military dimension, this is becoming an increasingly hard sell within Mauritius. Firstly, because the dimensions of the runway and jetty (and other developments) are similar to those proposed for Assumption Island, which the leaked agreement admitted had a military dimension. The agreement for Assumption Island even had clauses about whether or not Indian troops would fall under Seychellois or Indian military law. It was Indian military law.

Secondly, it’s becoming hard to explain why New Delhi is willing to spend Rs8.8 billion to develop an island of just 300 people, when in the past Mauritius itself had proved unwilling to spend much lower amounts. In 2003, for instance, Port Louis did not consider it worthwhile to upgrade the runway on Agalega after GIBB (Mauritius) Ltd offered to do it for Rs54 million. Or in 2011, when GIBB offered to do it for Rs120 million and Gamma Civic offered to do the same thing for Rs350 million. This is in addition to the fact that outside of the Mauritian government, nobody is bothering with such denials.

Thirdly, is the Mauritian government’s persistent refusal to make the 2015 agreement for Agalega public. India’s ex-foreign minister Sushma Swaraj stated that she had no problem making the agreement public, but Port Louis would have to agree to that too. “The ball has been in Mauritius’ court for a long time now. But they haven’t done anything,” says Makhan. When quizzed in parliament, Jugnauth insisted that because of a confidentiality clause in the agreement, “it is not going to be made public. That is what I can say, and I maintain what I am saying; I have discussed with India, I have discussed with the Prime Minister of India. I hope you do not doubt my word!”

Box 4: Why the Mozambique channel is important for India The choice of Agalega (and Assumption Island), and the identification of the Mozambique Channel as a chokepoint is dictated by the growing importance of the channel for New Delhi. The channel assumed strategic importance after Vasco da Gama crossed it in 1498 on his way to India. In the coming centuries, the Portuguese displaced Arab traders from the region which they used to supply slaves to Portuguese-owned plantations in Brazil. With the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, the importance of the Mozambique Channel diminished. However, the Mozambique channel has emerged as a key alternative to the Suez. Today, nearly 30 per cent of shipping in the Indian Ocean passes through the channel. “It has emerged as a vital chokepoint and when the ‘Ever Given’ disrupted shipping through the Suez for more than a week in 2021, it really underscored the importance of other sea lines of communication such as the Mozambique channel,” argues Makhan. With the Suez down, shipping was diverted through the channel.

But for New Delhi the channel became even more strategically important as international firms began looking for LNG deposits off the coast of East Africa. Eager to build relations with Mozambique, India sent ships to the channel to provide security when Maputo hosted an AU summit in 2003 and a World Economic Forum summit in 2004. In 2010 the US energy company Anadarko struck gold when its discovered extensive LNG deposits in the area leading to a scramble by international energy giants including ENI, ExxonMobil, BP, Shell, China National Petroleum Corporation and an influx of Indian firms as well including India’s Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) India Oil and Bharat Petroleum Corporation, which bought stakes in Anadarko’s holdings in the Rovuma basin.

Another Indian company, Essar Ports, has signed a 30-year deal to build a coal terminal at Mozambique’s Beira port. For India, which imports 90 per cent of its LNG from Qatar, the Mozambique channel offers a vital alternative for sourcing LNG without the political complications of the Middle East. “The sea off the Mozambique coast has now become a very sensitive area and no doubt everybody will want there to be lots of surveillance,” says Boolell. That is where India and Agalega come in: the states surrounding the Mozambique Channel have limited means to keep watch on the sea, while for India, which started jointly running P-81 surveillance flights with France via Reunion, Agalega means New Delhi no longer has to rely on French facilities.

While India’s growing strategic needs, evolving maritime doctrine, fear of China and the Assumption deal falling through mean that Agalega has become more important in New Delhi’s strategic imagination, the same cannot be said of Mauritius. With Mauritius continuing to insist on keeping all this a secret, the result is that the Mauritian public is largely in the dark not just about the regional geopolitics, but equally the risks that a small island-state like Mauritius faces. “The Prime Minister has an obligation to come clean about all this now and tell the Mauritian public the truth,” concludes Boolell. It also means coming clean about the risks of facilities hosted on Mauritian soil potentially becoming a target in a possible future conflict in the region. “This is not a remote possibility in case there is a conflict,” argues Makhan, “if the public does not know about what is happening in Agalega, how would they know about the risk?”

Publicité

Les plus récents