Publicité

Politics: The opposition leader’s seat: A political bargaining chip…

Par

Partager cet article

Politics: The opposition leader’s seat: A political bargaining chip…

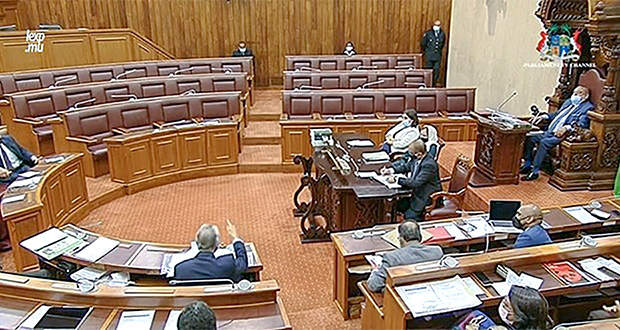

Recent days have seen a flurry of speculation of talks amongst the parliamentary opposition parties. Including the suggestion that appeared briefly, of the Labour Party taking back the opposition leader’s seat as part of a grand deal of dividing parliamentary posts with the other parties. So how has this post become a political football, and why does no one seem to want the job anymore?

- The bargaining

In recent days, a flurry of speculation has emerged about talks amongst the parliamentary opposition comprising the Labour Party (LP), MMM and PMSD. One of the possibilities that briefly appeared was about LP’s Arvin Boolell taking back the seat of leader of the opposition as part of a wider deal amongst opposition parties to divide parliamentary posts amongst themselves. A possibility that was put paid to by Boolell himself on March 7. So, what has led to that parliamentary seat becoming the subject of political negotiations?

The roots of the current crisis go back to 2021. The 2019 elections saw Boolell becoming leader of the opposition. However, in February 2021, the MMM and the PMSD broke with LP over the question of backing the latter’s leader and former prime minister Navin Ramgoolam as the opposition’s candidate for prime minister at the next general elections. This led to Boolell quitting his post on March 1, 2021, briefly leading to confusion as the MMM and PMSD leaders went to the State House in Réduit to discuss the allocation of this post with the president, Pradeep Roopun. The stark to the MMM and the PMSD was to formally announce a bloc within the opposition to make way for a reluctant PMSD Xavier-Luc Duval to take up the post.

One reason why the post of opposition leader continues to resurface as a potential bargaining chip is the complicated picture that the parliamentary opposition presents. Section 73 (2) of the Constitution is quite explicit; it outlines two ways in which this question can be settled; “where there is one opposition party whose numerical strength in the Assembly is greater than the strength of any other opposition party, the member of the Assembly who is, the leader in the Assembly of that party”. Under this section, Rajen Narsinghen, senior lecturer in law at the University of Mauritius, explains, “there is the numerical principle. At present the Labour Party has more seats than any other party in the opposition under this section, you would have to appoint somebody from the Labour Party.” It was under this rule that after the 2019 elections, Arvin Boolell of LP took up the post.

However, the other consideration under this section of the constitution is that “where there is no such party, the member of the Assembly whose appointment would, in the judgment of the president, be most acceptable to the leaders in the Assembly of the opposition parties”. What that means, Narsinghen adds, “is that although the Labour Party is the single largest party within the opposition, since the MMM and the PMSD came together, that changed the composition”. This is the root of the problem. While on paper, it seems that LP should occupy the seat, the other two parties coming together tips the balance in their favour. “The ones commanding the majority in the opposition right now are the MMM and the PMSD, so the president cannot just give the post back to the Labour Party,” says lawyer Sanjay Bhuckory.

- When numbers have and haven’t worked

Mauritius’ parliament has a rich history when changes within the opposition have forced changes as to who holds the opposition leader post. The 2005 elections saw the MMM and the MSM emerging as a unified opposition. However, a year later, in 2006 that de facto alliance broke down. Until that point, despite having more MPs in the opposition, the MSM allowed MMM’s Paul Bérenger to hold the post. As relations between the two parties broke down, the MSM flexed its muscle and the post shifted to Nando Bodha. However, another year later in 2007, two MPs defected from the MSM, weakening it within the opposition ranks and depriving it of a majority and allowing the post of opposition leader to end up with Bérenger and the MMM once again.

More recently, in December 2016, when the PMSD led by Xavier-Luc Duval developed differences with the MSM, ostensibly over the Prosecution Commission Bill that would have handed the MSM-led government direct control on legal prosecutions by the state, the PMSD quit the government. The party entered the opposition with more MPs than the MMM, who then was the opposition leader. So, Bérenger had to make way for Duval. These are relatively straightforward examples of where the tyranny of numbers made itself felt. “The problem is that our constitution envisaged a bi-polar parliament split between two parties and not a messy multiparty system like we have now,” Narsinghen points out. When such cases emerged in the past, it was not always numbers that carried the day.

In 1993, for example, a ruling MMM-MSM alliance broke down and led to the MMM going into the opposition. The trouble was that the MMM had more seats than those held by LP, whose leader Navin Ramgoolam was the opposition leader. But instead of using numbers to wrest the post away from Ramgoolam, the MMM allowed him to continue to make way for an eventual alliance between the two for the 1995 election. “The difference with that case was that in 1993 there was political will to reach such an accommodation,” says Ram Seegobin of Lalit, “today we have developed a configuration where LP is separate and opposed to the other parties and Arvin Boolell feels that the MMM-PMSD has more members than he has.”

The trouble right now, and why this situation is dragging on is that no one can just impose a solution on a divided opposition. “This is just jockeying for position with an eye to the next election,” says Bhuckory, “this is a question of pragmatism and until the whole opposition agrees, it cannot be settled.”

- Why no one wants the job

The other reason why the opposition leader’s seat is so readily being made available as part of an attempted political accommodation is that Mauritius is currently going through an unprecedented situation where no one seems to want the job. In 2021, for example, neither the MMM nor the PMSD said they wanted Boolell to quit as opposition leader. But he did. “The MMM’s attitude has been that they are not interested in the post,” says Seegobin, “even though, after the LP, it is the MMM that has the most seats in the opposition.” After the MMM passed on the post, it fell on the reluctant shoulders of PMSD’s Xavier-Luc Duval who insisted that he was taking up the post “for the time being”. At the beginning of 2022, with reports of the seat being offered back to LP, it does not seem in a hurry to take it back, citing section 73 of the constitution. It might be the first time, Seegobin continues, “that there is this kind of situation of total confusion within an opposition”.

There are two main reasons why no one seems too eager to hang onto the seat. The first is the realization that what is happening within the National Assembly is a bit of a sideshow. “While most people are talking about the constitutional aspect of this post, and it does come with constitutional responsibilities, few are talking about the political aspect of it,” Seegobin insists, “the leader of the opposition in Westminster systems is considered to be a shadow prime minister.” In this case, the main challenger to current prime minister Pravind Jugnauth, is widely considered to be LP’s leader Navin Ramgoolam whose party alone in the opposition is able to mount a challenge in the key rural strongholds of the MSM.

But Ramgoolam is not in parliament. “That is the elephant in the room, and while few are talking about it, it’s there staring everyone in the face. If they cannot agree on who within parliament should be the main challenger, and don’t agree on a common programme, it’s not surprising why they cannot agree on who should be in this post to represent them,” Seegobin maintains. Therefore, no matter who controls the post of opposition leader within parliament, what is certain is that most likely that person will not be seen as the main challenger to the government come the next election. That rubs away a bit of sheen off the post and makes it a less high-stakes affair than it normally is.

Now for the second problem: any leader of the opposition within the current parliament is constantly at the mercy of a divided opposition. “Putting yourself forward as a contender directly against the government is risky and you can be easily burned,” says Bhuckory, “in such an opposition there is just too much uncertainty and as opposition leader you would never know whether the other opposition parties would actually back you.” Having to take on the government, while at the same time constantly papering over disputes and disagreements within a fractious opposition is not a tantalizing prospect. “So far they have just settled by default on Xavier-Luc Duval, who leads the smallest party in the opposition,” says Seegobin, “this problem won’t be resolved anytime soon and as the next election nears you are still left with the intractable problem of who the opposition will put up as its prime ministerial candidate.”

- The opposition whip and PAC chair

A further complication is that offers about the leader of the opposition post and a grand bargain within the opposition have also been tied up with talks about who gets the post of opposition whip and the chair of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC), two other key opposition appointments within the National Assembly. While the MMM and the PMSD have reportedly offered to return the opposition leader post to LP on condition of dividing these remaining two posts amongst themselves, the problem is that deciding the fate of these two posts is wholly a matter of political accommodation.

Unlike who gets the leader of the opposition post, the constitution lays down no rules about how these posts should be allocated within the opposition. “Nowhere does it say that the opposition whip has to come from the same party as the leader of the opposition. It may be more practical to do so, but it’s not a requirement,” Narsinghen argues, “similarly who gets to chair the PAC is also not in the constitution. Both of these posts are creations of standing orders.” Standing order 69 mandates that the PAC be made up of nine members – a mix of government and opposition MPs – but by parliamentary practice, its chair has always come from the opposition. What this means is that if the negotiations over the opposition leader post – where the constitution does lay down rules about who gets the post – when it comes to these two posts, where no such hard and fast rules exist, any such talks are even more dependent upon the willingness of the opposition parties to reach a deal.

Narsinghen reaches back to 1969 to outline what such an accommodation could potentially look like. After LP and PMSD created a coalition in 1969, the opposition back then was equally divided between the IFB led by Sookdeo Bissoondoyal and a breakaway faction of the PMSD that each held six seats in parliament. Unable to decide who should get the post, they agreed on rotating the opposition leader post amongst themselves. “While a multiparty parliament and a divided opposition has complicated matters, such arrangements are possible,” he concludes. But provided that the opposition parties start looking seriously about what is actually at stake and demonstrating a seriousness to reach some sort of working arrangement amongst themselves.

Publicité

Les plus récents